The Soaring Journey: Amelia Earhart – Twenties to 1937

A Young Woman Drawn to the Skies

In the early 1920s, aviation was still in its infancy, and female pilots were virtually unheard of. Earhart, in her early twenties, lived in a world where social expectations for women were tightly constrained.

Early Twenties: Awakening to Flight

Amelia Earhart’s journey in aviation began with a transformative 10-minute plane ride with veteran pilot Frank Hawksin in December 1920 at an air show in Long Beach, California. She later reflected, “By the time I had got two or three hundred feet off the ground, I knew I had to fly.” (Live Science).

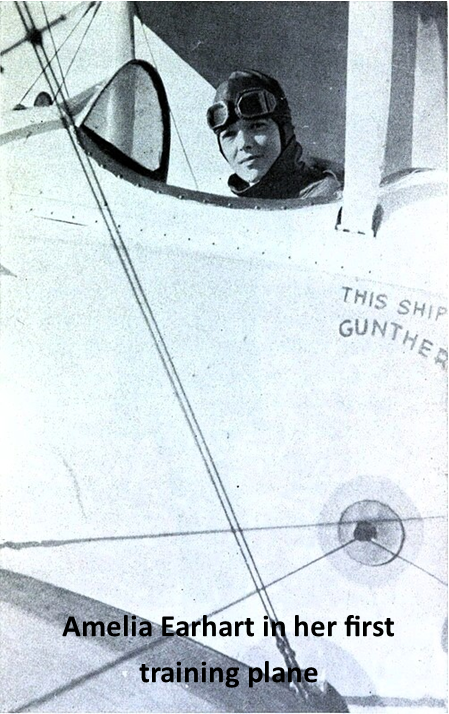

Within months, she had saved money for lessons with Neta Snook, one of the few female flight instructors in the U.S. Within six months, she purchased her first aircraft—a bright yellow biplane (she lovingly called The Canary) , with it, she broke the women’s altitude record in 1922, climbing to 14,000 feet. This was an era when aircraft were fragile machines of wood and fabric, so her achievement captured attention both in aviation circles and among women’s rights advocates.

Mid-Twenties: First Recognitions and Records

Earhart earned her pilot license in May 1923, becoming the 16th woman licensed by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (Live Science).

Late Twenties (1928): Atlantic Fame

In 1928, at age 30, Earhart journeyed aboard the Friendship as a passenger on the first transatlantic flight by a woman. Though she didn’t pilot the aircraft, the feat turned her into a global celebrity. Reporters compared her to Charles Lindbergh, dubbing her “Lady Lindy,” a nickname that stayed with her throughout her career. She received a ticker-tape parade in New York and was showered with media attention.

The publicity was overwhelming—parades, receptions at the White House, and a book deal quickly followed. Earhart understood the cultural significance of her visibility: she could inspire women by showing what was possible beyond traditional roles. During this period, she became a sought-after speaker and columnist, using her platform to advocate for women in aviation and other professional fields.

Early Thirties: The “Lady Lindy” Era

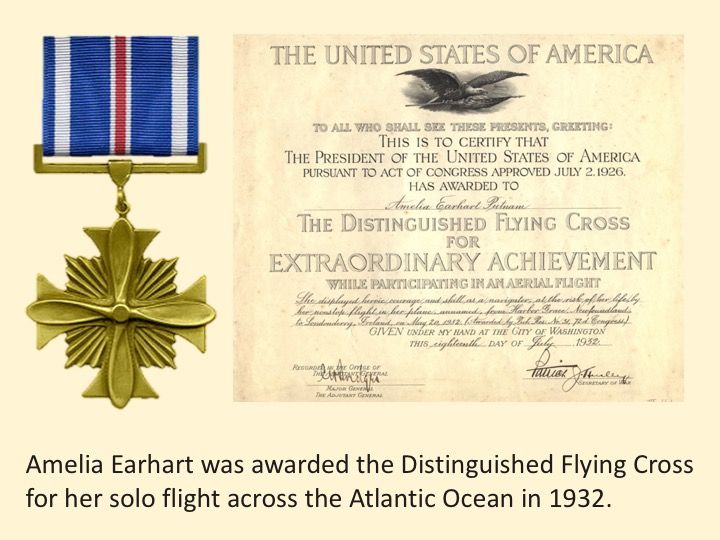

Solo Transatlantic Flight (1932): On May 20, she became the first woman to fly solo nonstop across the Atlantic, battling icy weather, mechanical problems, and exhaustion, she landed in a field in Northern Ireland after 15 hours—a feat that mirrored Charles Lindbergh’s journey exactly five years earlier. This daring achievement made her the first woman, and only the second person after Lindbergh, to do so. She was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross—the first woman to receive the honor.

Continental U.S. and Pacific Records: Her momentum didn’t stop there. In August of the same year, she became the first woman to fly solo nonstop across the continental U.S from Los Angeles to Newark. By 1935, she became the first person to fly solo from Hawaii to California—a particularly dangerous route over open ocean. These records not only demonstrated technical skill but also helped normalize the idea of women undertaking dangerous, high-stakes endeavors.

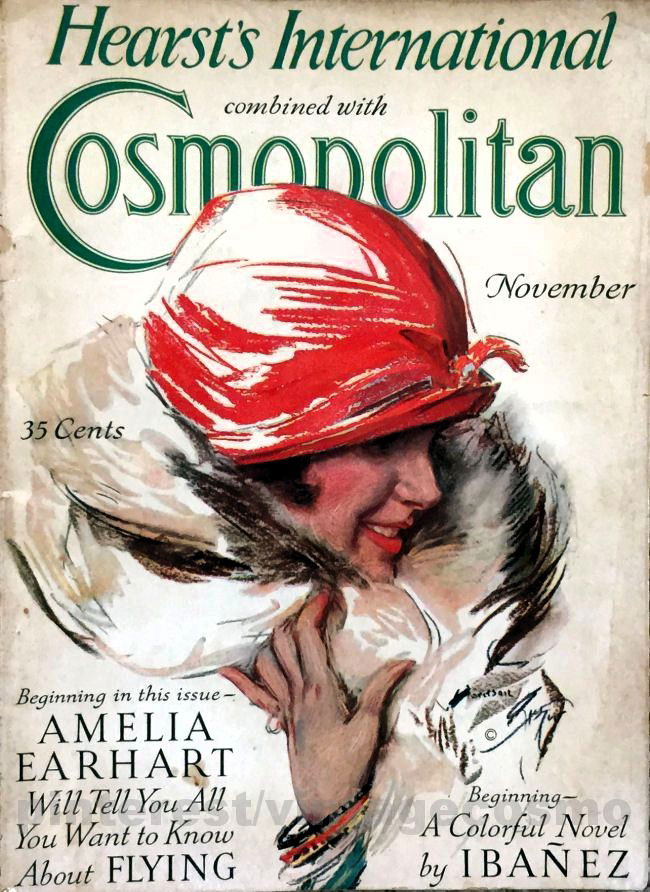

Alongside her flights, Earhart was also a prolific writer and speaker. During this period, she also became aviation editor for Cosmopolitan (1928–1930) where she encouraged young women to pursue bold careers and published two books: 20 Hrs. 40 Min. (1928) and The Fun of It (1932), the latter encouraging women to break societal norms.

Personal Choices and Partnerships

Earhart’s personal life reflected her progressive spirit. In February 1931, Earhart married publisher George Palmer Putnam (after reportedly six proposals) who went on to play a crucial role in shaping her public image. Yet she insisted on maintaining independence in her marriage, famously writing a letter to Putnam stating that she would not be bound by conventional expectations.

She remained committed to her career, even writing to him that she “shall not hold you to any mediaeval code of faithfulness”—placing aviation above conventional expectations. Their partnership was built as much on professional collaboration as personal companionship—Putnam helped organize her flights and public appearances, while Earhart focused on her passion for flying and women’s advancement.

Mid-Thirties: Preparing the World Flight

By 1935, Earhart was appointed a consultant in careers for women at Purdue University. Appointed as a visiting faculty member, she served as a career counselor for female students, encouraging them to dream beyond traditional boundaries. Purdue also helped finance her Lockheed Electra, the aircraft she would use in her final, ill-fated flight which she referred to as her “flying laboratory.”

The Fateful Final Flight (1937)

By the mid-1930s, Earhart wanted to attempt her most ambitious project yet: a flight around the world. While others had circumnavigated the globe, none had done so at the equator, which would be the longest possible route. This venture was not just about personal ambition—it was also framed as a scientific expedition, with her aircraft outfitted as a “flying laboratory” for research and navigation experiments.

Westbound Attempt and Ground-Loop Incident

Her first attempt in March 1937 ended in disaster when her Electra was damaged in a ground-loop accident in Honolulu. After repairs, she and her navigator, Fred Noonan, tried again in June, this time flying eastward. They successfully crossed South America, Africa, India, and Southeast Asia, arriving in Lae, New Guinea, with only the Pacific stretch left.

Eastbound Departure and Progress

Resuming their plan, they began again on June 1, flying eastbound from Miami. Over several weeks, they refueled across South America, Africa, India, and Southeast Asia, reaching Lae, New Guinea by June 29—at this point, 22,000 miles of their 29,000-mile journey had been completed.

Disappearance Near Howland Island

On July 2, Earhart and Noonan departed from Lae, heading to Howland Island—just 2,500–2,600 miles away. A U.S. Coast Guard cutter, the Itasca, waited offshore to assist, but poor radio contact and challenging navigation hindered help. Earhart’s transmission that they were "running north and south" along a navigational line was their last message.

Search and Loss

The plane is believed to have crashed roughly 100 miles from Howland Island, and the search—then the most extensive and costly in U.S. history—ceased after weeks with no trace found. Earhart and Noonan were declared lost at sea; Earhart was legally presumed dead on January 5, 1939.

Theories and Legacy

The Official “Crash-and-Sink”

Government investigators and most historians conclude Earhart ran out of fuel and crashed into the Pacific near Howland Island—a scenario supported by radio logs and search efforts.

Nikumaroro Castaway Hypothesis

TIGHAR proposes that Earhart and Noonan, missing Howland, may have landed on Nikumaroro (then Gardner Island). Artifacts—including shoes, Plexiglas fragments, and bones—found by expeditions support the theory, although no conclusive proof exists.

Other Speculations and Recent Efforts

Alternate theories—such as capture by Japanese forces—persist despite lack of evidence. Technological efforts continue: a recent sonar image captured by a private exploration near Howland has reignited interest, though experts caution that confirmation remains elusive.

Summary Table: Era Highlights

Period | Highlights |

|---|---|

| Early 1920s | First flights, altitude record, pilot license (1922–1923) |

Late 1920s (1928) | First female transatlantic flight as passenger; celebrity status |

Early–Mid 1930s | Solo records, writings, aviation advocate, publications, marriage |

1937 Final Voyage | Ground-loop crash; resumed eastbound world flight; disappearance June–July |

Post-Disappearance | Multiple theories; searches continue, enduring legacy |